Location

We are located at the corner of Sifaka and Melhisedek (Maheradika) in the Old Town of Chania.

Neighbourhood

Sifis Konstantoudakis or Sifakas

Sifis Konstantoudakis, or Sifakas, who gave his name to the Knives’ street, was a great fighter in the Revolution of 1821 in Crete and a member of “Filiki Eteria” (the secret organisation which began the Revolution). His real name was Sifis Konstantoudakis, but he became known as Sifakas because of his physique, booming voice, and personality. Sifakas was born in 1770 in Melidoni.

A great fighter, first in battles against the Turks, among the courageous chieftains during the Revolution of 1821, alongside his brothers, Sifakas was a protagonist and victor of many battles. He became known for his courage, bravery and patriotism and was honoured with the degree of Pentakosiarchos, meaning “ruler of 500 soldiers”.

In early 1823, Sifakas was sent to Kissamos to observe and combat the hostile movements of the Turks. There, he defeated and routed the enemies, who had made a surprise attack from the district of Selino and had massacred the Christians in the village of Pervolakia.

While in Kissamos, Sifakas fell ill with pneumonia and died on 23rd March 1823 after 13 days of illness, aged 52. He was buried with great honours at a large public funeral at Gonia Monastery in Kolimbari following a decision of the Provisional Administration of Crete.

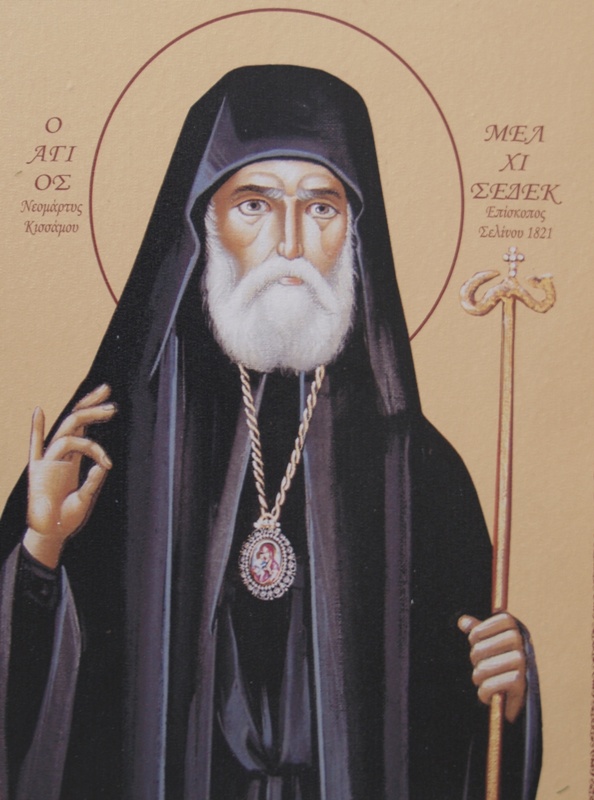

Melchisedek Despotakis

Melchisedek Despotakis was the Bishop of Kissamos and a member of “Filiki Eteria” (the secret organisation which began the Greek Revolution).

In 1821, with the beginning of the Greek Revolution against the Turks, there were conflicts between Christians and Muslims in Chania, leading to heavy losses on both sides.

On 19th June 1821, Melchisedek Despotakis became the first to be hanged by the Turks, from the plane tree on Splantzia Square. A monument next to the tree, which exists to this day, is dedicated to his memory.

Knives, Knife craftsmen and the Knife district

An integral part of the Cretan traditional costume, the knife was a favorite, not only as a useful tool, but also as an honoured weapon during the difficult times in Crete.

Since the Minoan era, the knife was a symbol of bravery. Evidence for this has been found in excavations around the island. There is written evidence of the use of the knife for military purposes in the Middle Ages, especially during the Revolution of Psaromiligkoi, a noble family, in the 14th century. The knife retains its ancient significance in the modern day.

During the Ottoman era, from 1669, the art of making knives experienced a boom in Chania. The first artisans were Turks, but soon Cretan artisans appeared who became specialised and created exceptional examples of their art.

Chania knife artisans (Maherades) settled right next to the ancient ruins, in the small moat that used to separate Kastelli from the rest of the city, which appears to have been maintained during the Ottoman rule. Before the German bombing during the Second World War, the two levels of the road reached up to Daskalogianni Street.

A great fighter, first in battles against the Turks, among the courageous chieftains during the Revolution of 1821, alongside his brothers, Sifakas was a protagonist and victor of many battles. He became known for his courage, bravery and patriotism and was honoured with the degree of Pentakosiarchos, meaning “ruler of 500 soldiers”.

In early 1823, Sifakas was sent to Kissamos to observe and combat the hostile movements of the Turks. There, he defeated and routed the enemies, who had made a surprise attack from the district of Selino and had massacred the Christians in the village of Pervolakia.

While in Kissamos, Sifakas fell ill with pneumonia and died on 23rd March 1823 after 13 days of illness, aged 52. He was buried with great honours at a large public funeral at Gonia Monastery in Kolimbari following a decision of the Provisional Administration of Crete.

The Cretan knife became famous not only in Crete itself, but also in the rest of Greece and in distant foreign countries. There are still a few younger craftsmen who have retained the art and artistry of construction of the handmade traditional Cretan knife and work with authentic traditional techniques and tools.

Sifakas Street was and remains the historic road of knife craftsmen in the city, which is why it is also known locally as Maheradika (“knife makers’ workshops”).

Splantzia

Near Kastelli and Koum Kapi, northeast of the old town of Chania, is the district of Splantzia. At the heart of the quarter lies the square on which the Church of Saint Nicholas stands. The church was part of an old Dominican monastery, converted during the Ottoman period to the mosque of Sultan Ibrahim. The church also served as a barracks for the Turkish janissaries at that time, providing them with a place for their daily prayers.

The church was later renamed “Chiougar Tzamisi”, meaning “Mosque of the Ruler”. It was where the sword of the Turkish dervish was kept, who was the first to enter the town and whom the Turks considered sacred and a worker of miracles. The minaret that was added to the church stands out from the others one can find in Chania because it has two circular balconies on the upper part.

Nearby is the Church of Saint Rocco, a round floor plan Venetian church which is no longer in use. St. Rocco was considered the protector of the inhabitants of Chania from cholera, a sign that the plague that had hit Europe in the Middle Ages did not leave Chania unscathed.

During the Turkish occupation, Splantzia was the town’s main Turkish quarter where many of its Muslim inhabitants lived. For the Turks, the square in Splantzia was something like the Fountain Square (in the Venetian Harbour) for the Christians, the place where all sorts of social and political events took place.